What Is Your Nation? A Chinese American Woman's Journey to Remember and Reclaim Identity

By Eleanor Xiaoxiao Mehta

W

hat’s your nation?” he asked her, his manner curious, interested, even friendly all of a sudden. “Arada…? Is you an Arada?” He waited. “Cromanti maybe…?” And he again waited. “Yarraba then…? Moko…?” (p. 167).

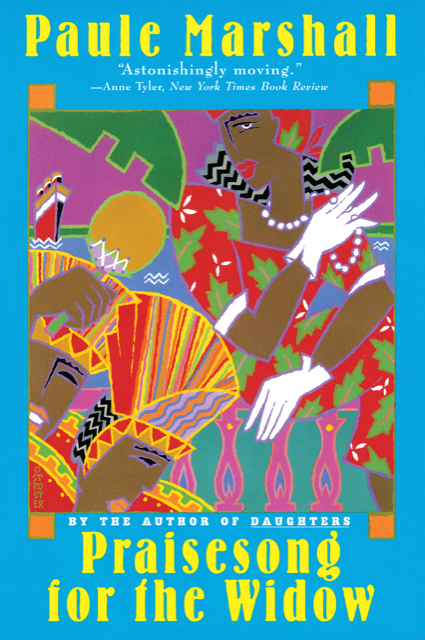

From Praisesong for the Widow by Paule MarshallWhen I first picked up Paule Marshall’s novel Praisesong for the Widow this past spring, I was not expecting the story to strike me in profound ways. In the novel, Marshall describes Avey Johnson, a Black, middle-aged, middle-class widow from New York and her unexpected journey of reconciling her roots and heritage in the Caribbean. As I read the book, different quotes transported me in time, taking me on a journey of my own remembering.

The question of “what’s your nation” is a question that has long troubled me. Unlike Avey, I was not born and raised in the States but moved with my family to Atlanta, Georgia when I was fourteen. Growing up in mainland China, I learned Chinese history starting from the creation tale of “Pangu” to the series of dynasties that led to the establishment of the communist rule. The history lessons spanned over 5000 years were taught throughout my K-8 education. I knew China as my nation.

Similar to Avey, I returned to China for a visit after becoming an adult in the States. A naturalized U.S. citizen and a self-assured American, I found my identity challenged by my relatives and locals who lived there. What resulted was an identity crisis that I still find myself continuously unraveling.

“I’m a visitor, a tourist, just someone here for the day,” [Avey] said lamely. “I was on the cruise ship that came in yesterday.” (p. 167).

Avey’s words echoed my experience.

That summer when I returned to China after college, I found myself disguising as a tourist in public. When I was with my American friends, I would hide the fact that I could understand and speak Chinese fluently. But when I visited my relatives, I behaved like a Chinese local. It was easier for me to be either Chinese or American, either an insider or an outsider, but being a Chinese American is the ambiguous in-between space too confusing for myself to figure out. However, the more I went back and forth between the two identities, the more tiring it became. At the end of my time in China during that summer, I couldn’t wait to return to the States.

The recent anti-Asian hate in the United States has given me flashbacks of what occurred to me during that summer. Only this time, it is no longer me choosing between the two identities, but others in society placing the “perpetual foreigner” identity upon me. Violence against one’s identity is always painful and once again, Asian Americans find themselves stripped away of their wholeness and scapegoated in the political discourses against another Asian country. Epitomized by the experience of Japanese Americans in the WWII internment camps, and followed by the experience of Chinese Americans during McCarthyism and that of Asian American soldiers during the Vietnam War, the Asian American life has long been tainted by a constant fear of rejection.

I first encountered this rejection when I moved to the American South as a teenager.

No one really cared that I spoke fluent Mandarin and could recite ancient Chinese poems from memory. The cultural and linguistic knowledge I had was not going to get me inside the cool crowds. I started envying the ABCs (American Born Chinese) in my high school, who spoke English with a southern drawl instead of a Chinese accent. I remember wishing myself to be just like them, who seemed to be as American as apple pie, instead of being a “FOBBY” Chinese girl, cultural shocked, and alone.

“You know,” he said, “I watched you good last night at the fete and I can’t say for sure but I feels you’s an Arada, oui. Something about the way you was doing the Carriacou Tramp there toward the end put me in mind of people from that nation.” (p. 252).

Avey meets Joseph, a local elder in the Caribbean, and she is bewildered by how Joseph seems to know her more so than herself. Joseph’s character reminds me of the Korean grandmother in the 2021 film Minari, who also acts as someone who helps the younger generations to find their true identity. The grandmother is first rejected by her second-generation Korean American grandson, but nonetheless she knows the truth that we all need to hear— those cultural memories of belonging still live in our bodies. Maybe, the question “what is your nation” is not about choosing, but about remembering and reclaiming. Countless Asian Americans have come before, and a great cloud of witnesses have interceded for us. We don’t know our way until we remember; remembering leads to restoration.

God is still doing the work of restoration within me.

Whenever I find myself straining to choose between what seems to be fragmented identities in order to belong, God reminds me who I am and whose I am- that I am whole, and I belong to Him. I am a Chinese American woman, and I am a child of God.

On this journey, God also asks me to care beyond my own nation. I think of nation also as ethnos, not just a political entity, but a people, a tribe, a family. Growing up, I was taught that family is everything. One can sacrifice everything for the sake of family, but those who are outside of the family are treated differently. In the wake of the Atlanta Spa shooting, I witnessed incredible solidarity from the Black community in support of fighting against anti-Asian racism. We are never meant to do justice alone. “If one part suffers, every part suffers with it” (1 Corinthians 12:26) rings true in our multi-ethnic and multi-racial body of Christ. God is asking all of us to expand our understanding of family beyond our own generation, our own church, our own ethnos. His vision of family has always been border-crossing and boundary-breaking. It is in this vision, I can empathize with Avey’s journey, while recognizing the stark differences in our ancestry. One was stolen, bought and sold with their freedoms taken away and entire memories of language and culture erased for generations; another came for the hope of freedom, leaving the home they once belonged and crossing shores to build another.

Finally, just as the moving wall of bodies was almost upon her, she too moved—a single declarative step forward. At the same moment, what seemed an arm made up of many arms reached out from the circle to draw her in… (p. 247).

At the end of Avey’s journey she partakes in this beautiful celebration called “Beg Pardon.” It is a picture of heaven where every nation and its people are remembered and embraced by name. The joy in the dance is irresistible for Avey to not being a part. It’s God’s invitation for you and me, as part of the greater Asian American nation, to join in the dance as well, to reclaim the identity that is uniquely ours and recognize the beauty in diversity and difference.

Photo courtesy of Penguin Random House

Eleanor Xiaoxiao Mehta is a 1.5 generation Chinese American living in Atlanta, Georgia. She is the daughter of Chinese mothers and grandmothers who have given her a love for storytelling and teaching. Currently she is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia, studying to receive her Ph.D. in Educational Theory and Practice with an emphasis on immigrant families and children with disabilities. You can reach her at eleanor.liu@uga.edu.

Help us continue the work of empowering voices. Give today.