Latest Articles

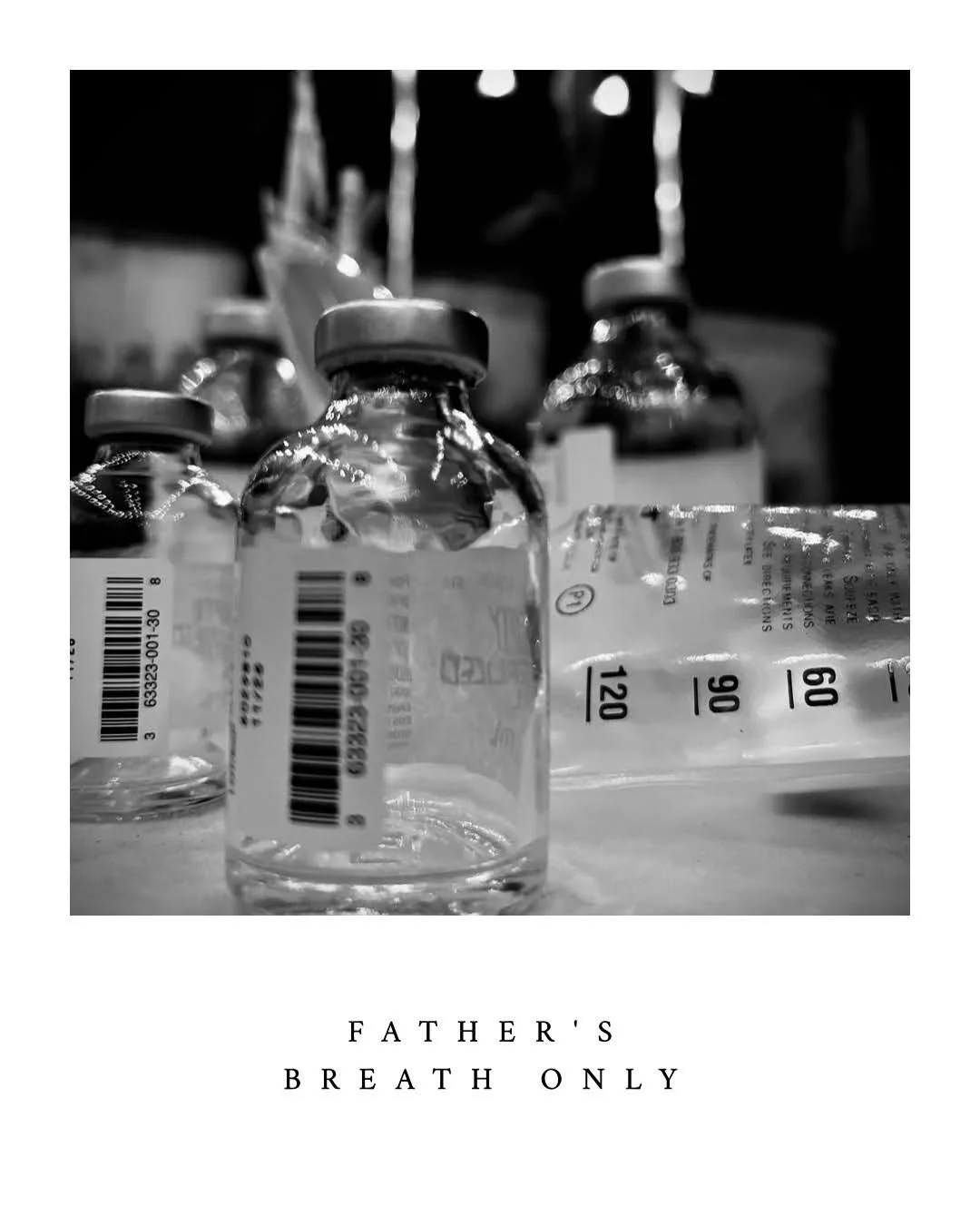

Father's PNEUMA is a very personal project for me. It was my attempt to reflect and process the devastating effects of Pulmonary Fibrosis - a debilitating lung disease that is taking my father's life. Through this piece, I explore the heart-wrenching journey of watching a loved one's gradual loss of breath and the overwhelming helplessness of such a condition.

How does one live faithfully to Jesus when you cannot stand your parents and do not know how to turn the ship around? We all come from varying degrees of conflict in our families of origin. It is my hope that my story can show a potential way forward and most importantly give Asian Americans permission to wrestle with the hardships of family relationships without shame.

In traditional Asian culture, and certainly in the Indian culture that I grew up in, honor is relational, communal, and duty-based. Our vocations, careers, lifestyles, and decisions in life may be scrutinized through an honor-based lens. While the Western society that many of us grow up in places great importance on self-expression and chosen respect, Asian honor translates to sacrifice, family reputation, loyalty, and obedience.

Our cultural heritage matters to God. Within our cultural heritage there are things we can learn about God. As Asian Christians we’re rarely told this. Perhaps we’re more often told that God wants us to set aside parts of our cultural heritage in the name of following Jesus.

But after this time of immobility, I've slowly come to realize that what I've received from my mother—my inheritance—is much greater than any sum of money: My very flesh, my whole life, was a gift from her.

Just as Jesus came as a baby approximately 2025 years ago to fulfill the hope of deliverance and reconciliation with God, there is a promise of a second coming of deliverance where all things will be once again made new. We must remember that this story of waiting is not a story of passive resignation or hardened indifference, or a fatalistic belief that nothing will change the trajectory of this cruel world’s demise. The story of redemption is not one of instant resolution, but of patient faith. And just because we cannot see what is to come does not mean we do not wait in anticipation and long-suffering for the story yet to be unraveled.

I took her withering hand in mine, the same hands that raised me up, the same hands that taught me how to read the Bible, the same hands that fed me purple yams, and I sighed. Because as a musician, I’ve been trained to hear what is both in sound and silence. Because as an actor, I’ve been taught to read between the lines. Because as a mixed child, I hold a distinct universe of two cultures, and yet, neither of them at the same time. Because as a Vietnamese girl who didn’t speak the language, I learned to navigate meaning in the space between understanding.

Asians from all sorts of ethnic backgrounds, immigration stories, denominations, and contexts came together as one body—distinct, yet unified by a common faith and shared heritage.

This was the mentality that my parents instilled in me when I was growing up. Grounded in cultural (i.e., Korean) and biblical principles, a part of this mindset was for my sister and me to be kind to one another as siblings. But make no mistake about it: in my family, the “family comes first” mentality disproportionately emphasized the need to honor our parents.

Those of us who grew up in an Asian American context know how shame often plays a prominent role in family and community dynamics. Major decisions can be made based on shame. Decisions like who you end up marrying, where you decide to go to school and study, and even what career you might choose to pursue can all be based on shame.

As Christians, we have the opportunity to experience God’s heart when we practice hospitality. In many ways, with its communal focus, rich food culture, and natural bent toward honoring guests, Asian culture uniquely positions us to share this kind of welcome with others. We have the opportunity to create spaces where people can enjoy a meal and a meaningful conversation. Where they can wrestle with a difficult thought, share their anxieties, or sit silent in grief. Where they can linger without an end time.

Here’s what we have learned. You do not drift into becoming a Jesus-centered church. You have to build it. We began asking, “How do we form a church where Jesus is truly central?” We found the answer in two things: discipleship and prayer.

As we learn how to tell our story with God, our voice becomes our superpower and points people to Jesus. It’s not just about knowing our story; it’s about telling it with the voice we have been given.

There is a reason that Jesus instructs his followers, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3). Once we become adults, our ability to embrace change and to open ourselves to new ways of thinking and living diminishes. But children have an inherent openness and malleability; with the exposure to the right kind of books, a child can be formed in ways that will last into adulthood.

As those who follow Christ, we believe in a God who provided daily bread in the wilderness (Exodus 16); a God who multiplied bread for thousands of people (Matthew 14:13-21), and a God who ultimately became bread to satisfy our deepest hunger (John 6:22-59). We can imagine it grieves God that anyone should be hungry; it should lead us to lament too. How do we wrestle with the weight of these realities and love our neighbors as ourselves (Matthew 22:34-40)?

I’ve learned that change rarely comes through arguments. My parents aren’t moved by stats. But stories, especially ones that echo their own, sometimes open something up. When I connect their immigrant struggles to those of others today, it sometimes softens them. Not always. But sometimes. What helps most is grounding our conversations in the life of Jesus—his humility, compassion, and refusal to chase power. When we remove Trump from the picture and just look at Jesus, the contrast is jarring. In the best way.

One of my favorite stories is Akira Toriyama’s manga/anime Dragon Ball. Loosely inspired by the novel Journey to the West, Dragon Ball follows a young boy named Son Goku, who enjoys martial arts which helps him to fight strong opponents and push his limits. While Dragon Ball never explicitly states its Asian setting, Toriyama prominently features Asian food, martial arts, and characters with dark hair and eyes. These examples may sound simple, but my younger self, who grew up on white superheroes like Superman, instantly felt a deeper connection to Goku as I experienced Asian representation for the first time.

do not forget

the ropes

suffocating the necks of

the Chinese

who sing the song of ages:

we can’t breathe.

Somehow learning that I have an Asian American accent felt fitting after learning snapshots of history. As if I inherited an unexpected gift or was mysteriously re-connected to the Asian Americans who came before me and struggled the same way. While I’ll probably always fumble over Korean, I know that regardless of my proficiency in Korean or English, I belong here.

Let us embrace the roots we’ve come from; And stand on the shoulders of our elders; The roots we grow from; The roots we rise from

We all have losses that have shaped us, from losing something we loved to lacking something (or someone) we needed. Only by taking the time to witness, name, and hold our Grief, can we find the strength to release it to grow into something more.

To become the church as it is called to be, the Asian American church should also engage in a historical reckoning of its own complicitous legacies, such as authoritarian and neoliberal complicity.

So then, can I, as an Asian American, trust Scripture? According to the wonderful contributors of The New Testament in Color, the answer to that question is “Yes!” Yet, not only I as an Asian American can trust Scripture, so too can African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and others.

Migration and immigration are among the key issues of our political moment. Immigration is a complex issue with more factors than are often considered in short sound bytes, but a clear call in the Scriptures is to care for the “sojourner in our midst.”

When injustices arise in the world, some churches speak up while others stay silent. In one of Jesus’ parables, a priest and a Levite see a man on the road who has been robbed, attacked, and left for dead. Their response is to pass by on the other side. What is the difference between them and a church that remains silent? Are they not the same? Both choose to disregard suffering and look away.

We celebrate this Advent, the birth of your son Jesus, and we also look forward to the 2nd Advent, the day when you will come again to make all things right, and to complete your Kingdom. Until then we ask for the strength of your Holy Spirit to help us to keep your commands, to live in truth, to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with you.

All of us are invited, even called, by God to make Jesus our hope. None of us are more worthy or less worthy to encounter God today. There’s no chart with God that puts some of us closer and some of us farther away. We’re all on the same ground. So, whoever you are, wherever you’ve been, welcome. God’s Spirit is here. Let’s meet him.

Today is the second Sunday of the Christian season of Advent. Advent means “coming” or “arrival.” We celebrate two advents of Christ during this season – and, really, every day.

We celebrate two advents of Christ during this season – and, really, every day. During Advent we look back at the first coming of Christ with so much thankfulness, and we look forward to the second coming of Christ with so much anticipation.

This document contains four worship services for the four Sundays of Advent. It is our desire that you use their basic ideas as a skeleton, or just incorporate certain sections for your own churches’ worship.